Secret Stash No Longer: LivWell Leads a Marijuana Movement

One of the largest vertically integrated marijuana distributors in Colorado is growing fast but faces tax and financing hurdles amid regulatory uncertainty.

LivWell has all the trappings of a typical retailer, with sales for Mother’s Day and Father’s Day, and loyalty points for customers. But the atypical parts are hard to miss. It took six years to find a bank that would work with the company—credit card companies still won’t—and executives say LivWell’s effective tax rate is well above 50 percent. That’s because LivWell’s product is marijuana.

More than half of U.S. states have legalized pot in some form, but the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration sees things differently. It gives cannabis Schedule 1 classification in the Controlled Substances Act, putting it in the same drug category as heroin.

According to Arcview Market Research, U.S. legal marijuana sales increased 37 percent in 2016, reaching $5.9 billion. With estimated illegal sales at $41.5 billion last year, that puts total market sales at roughly $47.4 billion. In this burgeoning industry, LivWell sits at the forefront. With 14 locations in Colorado, it defies the brick-and-mortar retail slump—revenue increased about 30 percent in 2016. That economic opportunity requires adherence to frequent regulatory shifts. Of LivWell’s 600 employees, more than 40 work on the security and compliance team to follow rules that include inventory control at the business’s dispensaries and 200,000-square-foot cultivation facility.

LIVWELL

Business: Among the largest vertically integrated marijuana growers and sellers in Colorado

Founder: John Lord, a former New Zealand dairy farmer

Footprint: 14 retail dispensaries, 200,000-square-foot cultivation center and 22,000-square-foot R&D site

Employees: 600+

Annual revenue: Estimated $100 million*

*Source: Cannabis Business Executive

“We’re creating a new industry, and we’re the most mature market that’s doing it,” says Neal Levine, the company’s senior vice president of government affairs. LivWell makes that clear with a tagline on its website: More than a cannabis dispensary—leading a marijuana movement.

A CONTROVERSIAL CROP

In the early 1990s, John Lord was a New Zealand dairy farmer with no plans to grow a controversial crop. He left the milk business to launch a baby-products manufacturer in 1995, which sold items such as safety seats and crib accessories to Walmart and Target.

Seeking a better location to expand his company, Lord moved to Colorado in 1998; 10 years later, he sold the Denver-based business. In 2010, he leased the building to tenants with a medical marijuana dispensary called Beyond Broadway. Lord formed a partnership with them and ultimately took full ownership to found LivWell.

By 2016, the company had acquired 11 more Colorado cannabis dispensaries. Many decided to sell, says Lord, because they couldn’t turn a profit due to the tax burden of Internal Revenue Code Section 280E. Originally intended for illegal drug traffickers, 280E prevents cannabis businesses from deducting ordinary business expenses such as rent and utilities (this applies only to “plant-touching” businesses, which grow, process or sell marijuana). That means the effective tax rate can exceed 50 percent—LivWell contends its 2016 rate was just under 80 percent.

“We learned very quickly that if you’re not running at some sort of scale, you simply cannot effectively operate under the severe tax penalty of 280E,” Lord says. After expenses, LivWell reinvests nearly all of its profits into the company’s growth.

Lord notes many small dispensaries exited because they struggled with industry regulations. Oddly enough, baby-product manufacturing prepared Lord for cannabis. That’s because his company had ISO 9001 certification, a widely used quality management standard that requires documentation. “I was accustomed to operating in a highly compliant industry, and it was not as large a leap for me compared to some others in the industry at the time.”

But he wasn’t accustomed to running a cash-only business. Banks didn’t want clients with product deemed illegal by the federal government. To pay the company’s taxes one year, Lord carried a duffel bag filled with about $2 million to an IRS office. Lack of banking also created vendor problems. “I would specifically ask these companies if they take cash, and they’d always say, ‘Yes, of course!’ Then I’d show up, and my duffel bag filled with cash that smelled like cannabis was no longer appealing,” Lord says. “Back then, most companies simply would not accept our cash.”

LivWell uses checks now—it opened accounts with a local bank and local credit union in 2015. But customers must pay with cash or debit card because credit card companies still won’t work with marijuana businesses.

MARKET STOKED, BUT POLICYMAKERS STILL HESITANT

When the company formed in 2010, Colorado was one of 13 states that had legalized medical marijuana, and legal recreational marijuana didn’t yet exist. Fast-forward to 2017: Eight states have approved legalization of recreational marijuana, and states with legalized medical marijuana have more than doubled to 29 at press time.

“While our revenue might be high, we’re just collecting all of that revenue and handing it to the IRS.”

NEAL LEVINE

SVP of Government Affairs, LivWell

This does not surprise LivWell’s Levine. He joined the company about two years ago but has worked on marijuana policy since 2003. During those early years, he saw a pattern emerge while lobbying for medical marijuana. “You’d have these state legislators who would treat you like their marijuana priest and would start confessing their college stories before they told me how they couldn’t vote for my bill,” Levine says. “I started to suspect that the opposition is really a mile wide but an inch deep. We’re not creating new cannabis consumers, we’re taking people out of the criminal market.”

“We opt for a cleaner look that evokes the interior of an upscale retailer of traditional goods, like cosmetics or jewelry.”

DIANNE BROWN

Senior Director of Sales, LivWell

LivWell has four locations for medical marijuana only, three locations for recreational and seven that sell both—including two new Denver spots, opened last year, which both measure nearly 7,000 square feet. The stores’ aesthetic bears no resemblance to the original LivWell shop’s decor of velvet curtains and unframed Bob Marley posters. “We opt for a cleaner look that evokes the interior of an upscale retailer of traditional goods, like cosmetics or jewelry,” says Dianne Brown, senior director of sales. “People have long assumed that cannabis consumers were primarily 20-something-year-old guys. Today, our fastest-growing consumer demographics are women and adults aged 45 and older.”

In 2016, roughly 79 percent of LivWell’s revenue came from recreational marijuana, a market that’s less than four years old. LivWell and other Colorado dispensaries started recreational sales in January 2014, after the state’s voters chose legalization in 2012. That year, Colorado and Washington became the first U.S. states to approve recreational marijuana, and they demonstrate how much state regulations can diverge. Take vertical integration: While Washington businesses are licensed either to grow or sell (but can’t do both), Colorado chose the opposite approach. The state required all cannabis businesses to grow at least 70 percent of their inventory. That changed in October 2014—Colorado’s recreational sellers don’t need to follow the 70 percent rule but medical sellers still do.

By next year, LivWell expects to grow 80 percent of the product it sells. Executives also say they have the only dispensaries in Colorado where consumers can purchase cannabis flower products from the brands of rapper Snoop Dogg (Leafs By Snoop) and country singer Willie Nelson (Willie’s Reserve).

THE COSTS OF BEING LEGAL

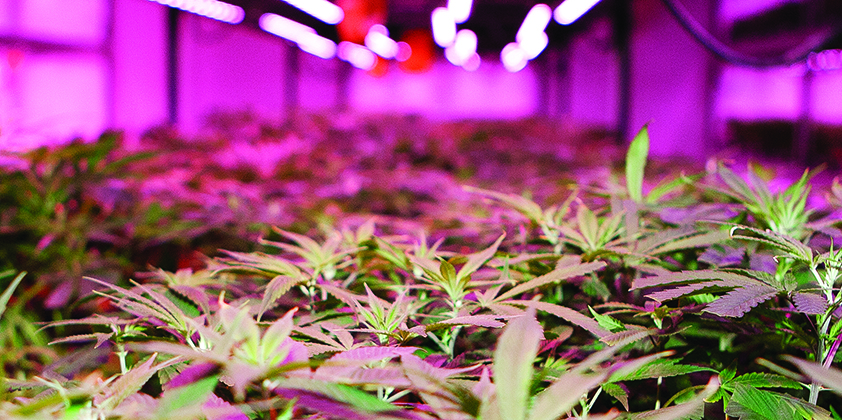

Approximately one-third of the company’s revenue is spent on cultivation-related costs. In addition to its main production center, LivWell has an R&D facility measuring about 22,000 square feet. As with all other Colorado licensed growers, every plant in its cultivation facility requires an RFID tag—part of what’s called “seed-to-sale tracking.” To provide more efficient lighting for its plants, LivWell invested more than $1.5 million in an LED system that helped it achieve the highest energy savings for a single lighting project in Colorado for 2016.

“That’s the difference between regulation and prohibition. A drug cartel won’t invest in LED green technology,” Levine says. He notes other differences: LivWell provides all employees with 401(k) plans and fully paid health insurance. It also contributed to the $200 million in taxes collected from Colorado’s marijuana sales last year.

According to Cannabis Business Executive, LivWell had $100 million in revenue for 2016 (executives won’t confirm whether that figure is accurate). Last year, the company landed on an Inc. list of “marijuana moguls,” a label that infuriates Levine. “There’s a common misperception that we’re all rolling in money,” he says. Although LivWell became “marginally profitable” in 2012 and stayed that way, Levine notes that the company would have “good profit margins” without the 280E tax burden. “While our revenue might be high, we’re just collecting all of that revenue and handing it to the IRS.”

LivWell has specific lobbying goals that don’t include legalization. Levine says the priority is a level playing field for the industry, meaning fairer taxation and better banking access. In addition to representing LivWell, he’s also a board member of the National Cannabis Industry Association and chairman of the board for the New Federalism Fund, which supports state-based regulation and the removal of 280E from the tax code. Bipartisan legislation is under consideration to address 280E, including the Small Business Tax Equity Act, co-sponsored by Republican Sen. Rand Paul.

Neal Levine, LivWell’s senior vice president of government affairs, discusses 280E on the Middle Market Growth Conversations podcast.

GROWTH IMPEDIMENTS

LivWell CFO Michael Raisch says 280E has limited the company’s ability to open new stores and attract potential investment partners. “There’s very little money left after tax to reinvest in the business. Which makes it difficult, even when you’re looking at friend-and-family kind of capital,” he says. “Everybody wants a return on capital and it’s hard for us to pay a current return because of that tax burden.”

Some investment firms are dedicated to the cannabis industry—including Los Angeles-based Casa Verde Capital, founded by Snoop Dogg—but they typically don’t invest in growers and retailers. Instead, they focus on ancillary businesses that support the cannabis industry with products and services.

That’s true at The Arcview Group, a marijuana angel-investment network. Although plant-touching businesses have received about half of Arcview investors’ funding, it’s mostly from high net worth individuals, says John Downs, Arcview’s director of business development.

Of the network’s approximately 600 investors, fewer than 15 percent are institutions such as private equity or venture capital. “But we are seeing a strong uptick in interest from them, especially family office managers,” Downs says. “Professional investors generally focus on ancillary companies because that’s where you get venture-scalable-type returns, the 100-times.” He says plant-touching businesses produce healthy cash flow, but returns are typically in the three-times range.

Downs says some investors worry about how the Trump administration will affect the marijuana industry. Their concerns mainly involve U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions, who has said, “Good people don’t smoke marijuana.”

“There’s very little money left after tax to reinvest in the business. Which makes it difficult, even when you’re looking at friend-and-family kind of capital.”

MICHAEL RAISCH

CFO, LivWell

Meanwhile, President Trump has stated his support for medical marijuana, including in a February interview during which he said, “I’m in favor of it a hundred percent.” In May, he signed a bill that controls federal spending through the end of September. It includes a provision that blocks the Justice Department from using funds to go after medical marijuana programs that follow state laws. But it does not protect recreational marijuana, and the administration’s plans for that market remain unclear.

When CFO Raisch joined LivWell a couple of years ago, he began attending meetings for a local group of financial executives. Early on, Raisch asked the group’s leader, “Should I tell people what I do? Should I be coy about it?” The response: Absolutely tell them.

“He said, ‘Quite frankly, a lot of them would like to do business with cannabis companies at the appropriate time.’” When the group hosted a panel discussion about cannabis in 2016, Raisch says it was the year’s most-attended event.

At LivWell, sales have reached record highs during the first half of 2017, with revenue up 25 percent compared with the same period last year. “We are very optimistic, despite headwinds that we face,” Raisch says. “We think it’s a good possibility we could be in five to seven states in the next two to three years, and that could involve as many as 25 to 35 new stores on top of ones we already serve.”

Levine says bans on marijuana won’t last. “Prohibition is essentially the Wild West. It gives an exclusive market to criminals, and we are occupying that space with legitimate, transparent, compliant businesses. People want that.”

S.A. Swanson is a business writer based in the Chicago area. She frequently covers technology.