Agtech Is Growing Up, but Is It Too Green for PE?

Private equity investors are closely watching advancement in agricultural technologies such as crop genetics and livestock monitoring tools, eager for ways to jump-start sluggish top-line growth in the ag sector.

Blockbuster mergers and acquisitions among agriculture industry giants have grabbed headlines for the last several years. But while Bayer courted Monsanto, and Dow and DuPont moved closer to merging, young agricultural technology companies were proliferating.

This sector, dubbed “agtech,” started turning heads in 2013, the year agriculture conglomerate Monsanto announced it would pay nearly a billion dollars to acquire The Climate Corporation, a provider of weather data and crop insurance to farmers. (Climate Corp. sold its insurance arm in 2015.) The price tag suggested that the sector—made up of companies using technology and data to improve the efficiency of farming—was ripe for investment.

Four years later, private equity investors are closely watching. While only a few specialized firms have begun opening their checkbooks for an outright purchase of an agricultural technology asset, some ag-related PE portfolio businesses are employing these tools to gain efficiencies on the farm.

Venturing In

There’s an increasingly urgent need for technological solutions to agriculture challenges. Global population growth and middle-class expansion in countries like China and India are driving the demand for more food. Meanwhile, urbanization, overuse of arable soil, and depletion of freshwater sources are straining the ability to produce it.

“You’ve got both increasing demand at the same time you have potentially decreasing supply, so the fundamental macro here is increasing prices for agricultural commodities over time,” says Eric O’Brien, co-founder and managing director of Fall Line Capital, a private equity firm that invests in farmland and agricultural technology businesses.

The solutions agtech companies are putting forth are wide-ranging, addressing aspects across the farming cycle—from the genetic makeup of seeds to how food is transported to consumers. They can include everything from enhanced soil that improves crop yields, to sensors that increase irrigation efficiency, to software systems that aggregate and analyze data to assist farm management.

Private equity firms typically look for proven business models and steady revenue sources, but many agtech companies have yet to prove that their technology works or to turn a profit.

“You have a lot of VC-backed companies, but it’s really sporadic in terms of the private equity groups that have investments in the agtech sector,” says Patrick Seese, managing director of Integris Partners Ltd., an investment bank whose focus areas include food and agriculture.

Venture capital investment in agricultural technologies increased exponentially between 2012 and 2015, reaching $4.6 billion before slipping to $3.2 billion in 2016, according to a report from AgFunder, an agtech investment platform that publishes research on the sector.

The dip reflects a decline in investment in bioenergy, drone technology and food delivery. It also coincides with a 10 percent drop across global venture capital markets overall, attributed to a sensitivity to high valuations and a weak environment for public exits. Agricultural technology companies have been slow to go public, which has dampened enthusiasm among investors who expected the market to develop more quickly, says AgFunder co-founder and CEO Rob Leclerc.

“It’s sort of like 1995 for the internet,” Leclerc says. “We can think about what the future of agtech would look like 20 years from now, but there needs to be a whole bunch of technological development to get there.”

Even companies mature enough for private equity investment pose a challenge. Getting products into the hands of farmers requires resources investors often don’t have: a sizable sales force, advertising muscle and time for a new product offering to gain acceptance.

“It’s going to be a pretty unusual private equity investor that has the infrastructure in place to get products into the market,” says J. Powell Carman, a partner at the law firm Bryan Cave, who has worked on a number of acquisitions and divestitures for biotech and agribusiness companies. “Without that, it’s going to be hard for an investor to capture the margin to get the return on their investment.”

“It’s sort of like 1995 for the internet. We can think about what the future of agtech would look like 20 years from now, but there needs to be a whole bunch of technological development to get there.”

ROB LECLERC

Co-founder & CEO, AgFunder

Not Quite a Revolution

Fall Line’s O’Brien estimates about a dozen investment firms are focused on agtech, while Integris’ Steese puts that figure even higher, at 15 to 20, with another eight to 10 firms fundraising as of July.

Most of that cohort is early-stage investors, but Fall Line is among the middle-market firms integrating agricultural technology investments into their portfolios. It primarily targets underperforming farmland but has allocated a portion of its fund to agtech. That allocation is flexible, allowing Fall Line to invest when it sees opportunities and to pull back should the sector face a downturn in the future.

The nine agtech companies within Fall Line’s portfolio strategically complement its farmland investments, helping it source and underwrite land and manage its farmland holdings.

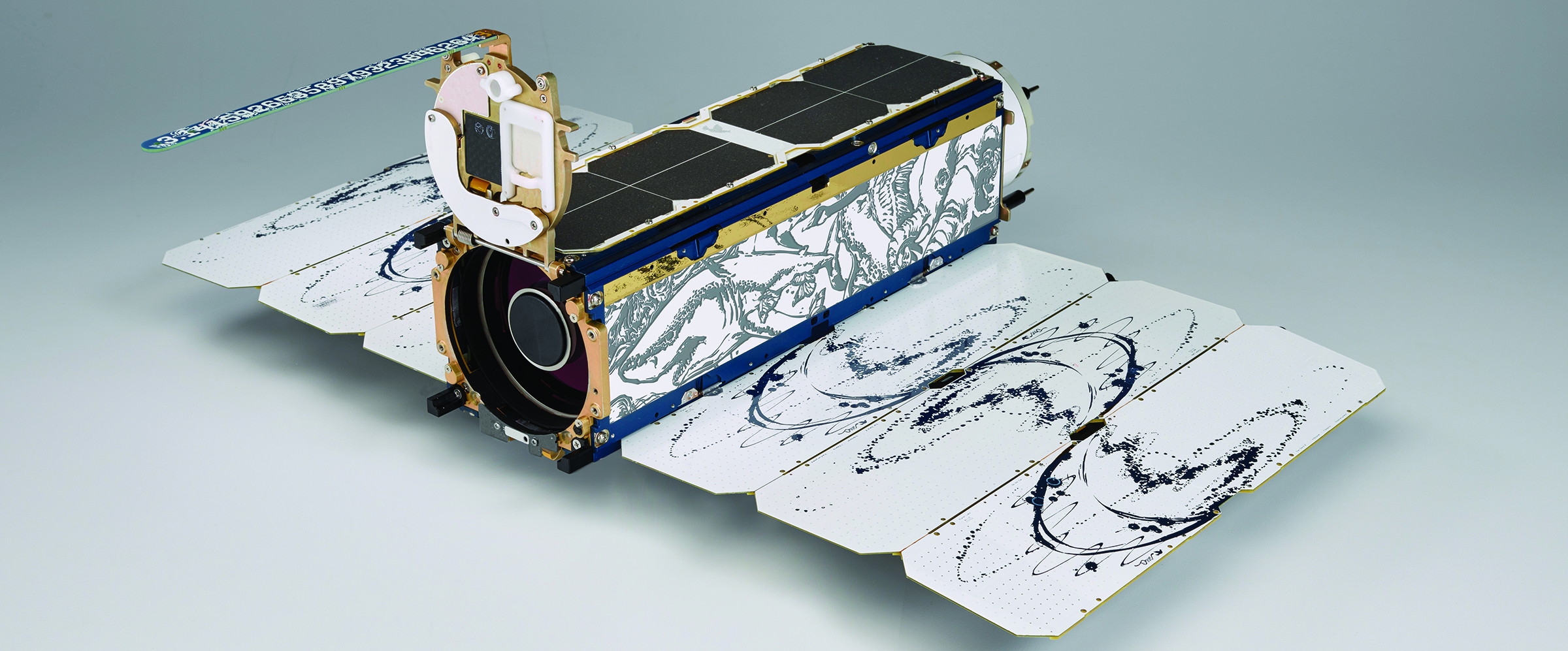

In 2015, Fall Line invested in Planet Labs, which has more than 150 high-frequency imaging satellites. Fall Line uses Planet’s tools to help evaluate new farmland investment opportunities, including how land has been managed during previous seasons; for existing holdings, it can monitor fields on a daily basis, detect changes, and assess overall crop health.

Another investor, AGR Partners, targets mature agribusiness companies, but it tracks developments in agtech with an eye toward introducing new technologies into its portfolio companies.

“When we think about agtech, we don’t think about it as a revolution. It’s just incremental, slow, 1 or 2 percent gains on what are big production systems,” says Daniel Masters, a managing director with the firm.

Among AGR’s portfolio companies is New Zealand-based Tru-Test, which helps improve farm productivity through livestock tools and systems. The company’s wide-ranging products include electronic identification systems to help farmers track herds using an online management tool, and weigh scales to measure and spot problems among individual animals. Electric fences, milk tanks and milk cooling systems are among its other offerings.

“There are some trends and technologies that are really going to fundamentally change the landscape around agtech.”

ERIC O’BRIEN

Co-Founder & Managing Director, Fall Line Capital

Promising Innovation

Agricultural technology companies that ultimately attract private equity investment will be those with offerings farmers can actually use. Millions of dollars have been invested in information and data retrieval technologies, yet 40 percent of rural Americans lack access to high-speed internet, notes Integris’ Seese. That makes seed technologies or hydroponics, for example, potentially more useful than drones or farm management software.

“Farmers have to adopt these technologies and show them to be sustainable. That’s when private equity money will start flowing in,” Seese says.

Crop technologies may be among the most promising for future private equity investment. Startups in this category raised $523 million across 61 deals in 2016, according to AgFunder. Among them are environmentally friendly pesticides and fungicides, known as biologicals, which can help protect crops from insects and weeds, increasing yield while making it easier to stay organic. Also included are technologies like gene editing and techniques to enhance soil to improve crop growth.

Another technology disrupting agriculture is robotics. Startups like GV-backed (formerly Google Ventures) Abundant Robotics, which developed an apple-picking robot, are using these technologies to tackle complex tasks, or to act as a substitute for human workers amid minimum wage hikes and immigration restrictions.

Other robotics applications are geared toward plant health. Blue River Technology, backed by growth capital investor Pontifax AgTech and others, uses computer vision and robotics to inspect and spray plants individually, rather than saturating an entire field. The company claims its technology enhances weed control and can dramatically reduce the use of chemicals, earning it a place on Inc.’s 2017 “25 Most Disruptive Companies of the Year” list.

Seeding the Future

In 2016, 670 investors backed 580 agtech deals, AgFunder data shows, and the venture capital support is helping startups to mature and prove the effectiveness of their technologies.

Companies with late-stage funding are beginning to acquire younger agricultural technology businesses, which could hasten their growth and make them attractive to private equity investors. Acquisitions of agtech companies by middle-market firms with established sales channels can help overcome a major challenge within the industry—getting new products to market.

For the past several years, large industry players have been busy with their own M&A proceedings, which has distracted them from pursuing innovation and sidelined a source of competition.

That’s given younger startups a chance to grow, priming them to be future private equity targets, says Fall Line’s O’Brien. Rising crop prices could also help. Low commodity prices have made it difficult for farmers to turn a profit, creating a tough environment for agtech companies looking to grow.

“I think there will be an interesting growth equity and private equity expansion opportunity for those companies,” O’Brien says. “That’s probably between two to three years out, based on the momentum that we’re seeing among the quality earlier-stage companies.”

Agtech assets carved out during the large mergers may also appeal to private equity buyers looking to back them as independent companies. O’Brien sees an opportunity for investors to partner and take advantage of new technologies to compete with corporations like Syngenta and Monsanto.

“I think we’ll see interesting syndication opportunities between groups at different stages and different expertise coming together for what I think will be a pretty interesting segment for private equity over the next 10 to 15 years,” he says. “There are some trends and technologies that are really going to fundamentally change the landscape around agtech.”

Kathryn Mulligan is the associate editor of Middle Market Growth.