Trading in Turmoil

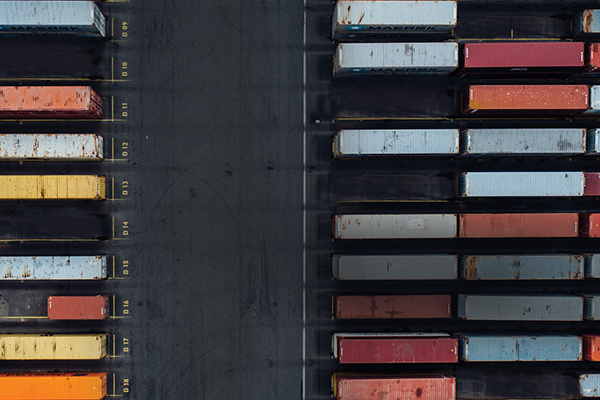

Abruptly announced tariffs, trade disputes and related policies are forcing thousands of midsize U.S. companies to respond to a new set of questions from investors.

To some midsize companies caught in the crossfire, international trade policies are starting to feel like a pinball machine: random, cascading and pointless.

Kal Beidas, board member and former president of Aetna Bearing Company, based in Livonia, Michigan, has long had smooth working relationships with precision bearing manufacturers in China. The quality of their products is essential to Aetna’s finely engineered parts, sold to customers in industries ranging from agriculture to automotive. Swapping in a new supplier simply on the basis of price and politics could undermine Aetna’s goals for growth, product design and quality.

Trying to sidestep tariffs costs Aetna time, money and energy; complicates planning; and infuses discussions with investors with a newly urgent factor. The company finds itself redirecting resources to figure out which high-quality products might be less expensive to source from suppliers in other countries—and how much it will cost to reconfigure contracts, shipping and logistics, especially if the Trump administration changes course. Further straining Aetna’s resources are the lengthy negotiations with customers around passing on a portion of the tariffs. Aetna is focusing on the big picture: Finding and vetting new suppliers is probably smart in the long run anyway.

Like Beidas, company leaders and investors are on edge as they feel out the tipping point where the cost of securing new, less expensive suppliers outweighs the transition costs and hassle. Abruptly announced tariffs, trade disputes and related policies are forcing thousands of midsize U.S. companies to navigate a trade regime that is constantly under construction. No sooner do firms learn one workaround when another barrier pops up.

LITTLE NOTICE, LESS PRECEDENT

The tariffs and related trade policies have been announced with little notice, short deadlines and with seemingly scant concern about the practical and financial fallout for companies.

The escalating trade war commenced in January 2018, when the Trump administration announced it would apply tariffs to solar panels and washing machines imported from China to offset what it claimed were below-market prices skewed by Chinese government subsidies. In April, China announced its own tariffs, on the food commodity sorghum, purportedly to combat dumping by U.S. suppliers. Dumping undermines local producers and skews market rates. Tariff ping-pong took off from there, with each country escalating the scope and amount of tariffs.

The debate about tariffs has been complicated by the administration’s claim that the extra expense applied to certain imports would not ripple through to producer costs or consumer prices. In fact, economists do detect rising prices due to the tariffs.

By mid-2019, hundreds of products were included in the broadly written U.S. tariffs, though exceptions are rampant. For example, while the book publishing industry sorts out the complications, it was announced in late August that Christian Bibles were exempted.

“ONCE YOU INVEST IN THAT MOVE, YOU AREN’T GOING TO MOVE THAT CAPACITY BACK TO CHINA AT THE DROP OF A HAT.”

BRIAN BUNKER

Managing Director, Asia, The Riverside Company

While large companies have the luxury of assigning teams to sort out the implications of tariffs, midsize companies face hard decisions about how to redeploy resources to hire experts to analyze, strategize, renegotiate and reorganize around the new rules.

LOOKING BEYOND CHINA

The element of surprise is an unwelcome factor in the Trump administration’s trade war with China. It’s not just that the tariffs are inflicted, but that every decision and every deadline seem to be written in invisible ink.

In some cases, company leaders go through the effort to confirm to themselves, customers and investors that they need to stay the course with Chinese suppliers. For some, the parts and materials they need are not available in the U.S.

“Some contracts are cut in stone but are conditioned on things outside our control. We give our customers options,” Beidas says. “If we don’t view it as a permanent tariff, and if we think that tariff is likely to be among the first to fall off once the U.S. and Chinese politicians reach an agreement, we want to offer customers options as to how they handle it now.”

For investment firms with large portfolios, tariffs can impact multiple holdings at once and raise questions about sourcing relationships. About 10 of the 70 companies in the portfolio of The Riverside Company, a private equity firm headquartered in Cleveland, are hit hard by the China tariffs, according to Brian Bunker, a managing director at the firm. That translates to about $30 million in imports that have been affected by tariffs of 10% to 25%. Shifting swiftly to suppliers in Taiwan has added retooling and related contract and logistics costs for those companies, but it is also softening their long-term risk, Bunker says. “Once you invest in that move, you aren’t going to move that capacity back to China at the drop of a hat,” he adds.

If there’s a silver lining to the hailstorm of tariffs, it’s that the near-daily headlines have made everyone keenly aware of new opportunities. Companies, investors and advisers say that alternative suppliers, from Taiwan to Mexico, are wasting no time in welcoming U.S. companies of all sizes.

“Many of our clients are committed to China for the long term,” says Bob Oberlies, who chairs the Asia practice for Minneapolis-based law firm Fredrikson & Byron. “But China has been swiftly moving up the value chain and is less interested in being the manufacturer of the world for lower- technology products.”

As labor and other prices rise in China, U.S. companies have increasingly turned to second- and third-tier cities within China, and to other countries, he says. “Each new wave of tariffs is forcing them to diversify faster and more broadly.”

But could tariffs dog new deals? That’s the rub, says Oberlies. “The U.S. administration’s trade policies are not limited to China, so it’s not entirely clear what countries will be ‘safe’ from future tariffs,” he says. “The U.S. has indicated it will be looking at Vietnam. Mexico has had its own issues, with U.S.- Mexico relations hitting several rough patches over the past couple years. Accordingly, we’re helping clients expand their supply chains into a broader group of countries, and to build backup plans for the backup plans.”

ASKING THE RIGHT QUESTIONS

By the time the second round of tariffs on Chinese goods gusted in this summer, firms had barely digested the implications of the first round. “In late 2018, when a lot of the clients we were working with weren’t sure how to react to it, some overpurchased inventory. Now they have a strain on liquidity,” says Claudine Cohen, principal and Northeast lead for the transactional advisory practice for New Yorkheadquartered CohnReznick.

Trade skirmishes are erupting on so many fronts that the Peterson Institute for International Economics constantly updates its timeline of the countries and products involved, and when the tariffs go into effect.

The turmoil is becoming part of the landscape, albeit one that’s constantly evolving. “Now, it’s like we’ll wake up and see what they’re threatening today,” Cohen says.

Doug Pallotta, a partner with San Francisco CPA and advisory firm OUM & Co., has seen clients impacted directly by the fast-moving trade developments. “One manufacturer we work with had a piece of equipment on a boat, headed for installation in their U.S. factory, and the price tripled while it was on the water,” he says. “But even then, it was cheaper than what they’d have paid in the states. There can be a compelling price differential.”

The policies are so sweeping and tenuous that they create a riptide that can take down seemingly solid deals.

Joan D. Hellmer is managing partner of a Radnor, Pennsylvania-based independent sponsor that works closely with family offices seeking to invest in family-owned companies.

Hellmer spent several months and tens of thousands of dollars assessing the likely effect of the tariffs on a potential investment: a home improvement distributor that commissions its own brand of cabinets and supplies, almost all from Chinese manufacturers. Hellmer hired a platoon of lawyers and export consultants to pinpoint exactly how tariffs would affect contracts and prices. For example, if a load of goods was purchased and partly paid for as it was loaded onto a ship, and a round of tariffs went into force while the shipment was on the water, at what point and to what degree would the tariffs be added to the customers’ price?

“We found out how many accommodations the manufacturers in China are willing to make to keep the business,” Hellmer says. “Some would even offset the tariffs almost dollar for dollar.”

But that wasn’t enough. Hellmer didn’t believe the firm could deliver a sufficient return to investors due to the unpredictable trade war and the likelihood that the distributor would be forced to pass on substantial accumulated costs. One of the potential investors walked away and the deal fell apart.

“This is a new thing included in due diligence,” Hellmer explains. “This used to be one of the last pages of the due diligence deck and now it’s at the front. People want to know how you’re prepared for this and you have to provide the information in a digestible and educated manner. What do tariffs mean for a company’s earnings, for shifting risk, for a competitive position? Everybody is going to ask those questions.”

GLOBAL TRADE’S MANY FRONTS

“THE MIDDLE MARKET IS CAPABLE OF REACTING MUCH FASTER TO BIG DISRUPTIONS. THE BIG PLAYERS MAY HAVE THE RESOURCES AND MAY HAVE SOME INFLUENCE OVER SOME POLITICAL DECISIONS, BUT SMALLER ONES CAN REACT MORE QUICKLY.”

SVEN JOST

Partner, BPM

While the U.S.-China trade dispute grabs the most headlines, it’s one of many issues impacting companies with global supply chains.

The impending decoupling of the U.K. from the European Union, known as Brexit, is a tempest in a teapot, say advisers. While the political process has been stop-and-go, it is at least a process with a defined goal.

The U.K.’s erratic approach to Brexit has already prompted some midsize companies to simply move their European offices or relationships to Ireland, says Sven Jost, the partner who oversees transfer pricing services for San Francisco-based accounting and advisory firm BPM. In his view, Brexit confusion stems not from the goal but from how to achieve it.

“It’s not the same as the China tariffs because it’s taking more time to unfold,” he says.

The Trump administration’s tariffs extend beyond China and have hit products from numerous countries and trading blocs. Meanwhile, the renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement, now known as the USMCA, has introduced changes to tariffs on goods traded among the U.S., Canada and Mexico.

The various tariffs are one consideration during a company’s valuation, but they are superseded by bigger factors, Cohen says. Strength of management teams, long-term growth trends, material availability, demographic trends and the looming recession are all deeper currents than political whims. The recreational vehicle industry, for instance, rode high on a tsunami of retiring baby boomers. Now, tariffs are just one factor deflating its momentum, she says.

Eventually, the dust will settle. When it does, midsize companies might just emerge as the surprise winners, predicts Jost.

“Right now, the middle market is squeezed, but it has a huge advantage,” he says. “The middle market is capable of reacting much faster to big disruptions. The big players may have the resources and may have some influence over some political decisions, but smaller ones can react more quickly.”

Jost suggests that, with the right guidance and capital, middle-market companies could weather the trade war and come out on top. “As the dust hopefully settles, one way or another, there may be midmarket players who come out of this a lot stronger, especially if you have a couple of strategic investors on your side to help you maneuver through it.”

This story originally appeared in the November/December print edition of Middle Market Growth magazine. Read the full issue in the archive.

Joanne Cleaver has been covering entrepreneurship and business growth for over 30 years for national media, as both a staff and freelance journalist. Read more from Joanne at www.jycleaver.com.