The Future of Logistics

Reorganizing suppliers, new technology and talent shape supply chains.

Business supply chains were massively disrupted by the COVID- 19 pandemic as governments sealed off ports and closed factories. Even today, the delays caused by lockdowns are still felt off the coasts of major cities around the world. As a result, companies are re-evaluating their supply lines and, in some cases, bringing operations closer to home, adopting new technologies and hiring talent to reinvent themselves.

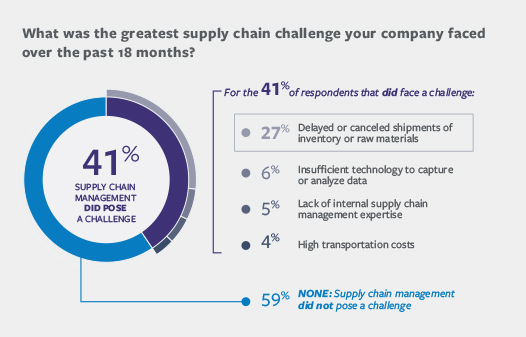

Still, supply chain issues continue to grip the middle market. Nearly 30% of respondents to a recent ACG survey cited delayed or canceled shipments of inventory or raw materials as the biggest challenge posed to their supply chain over the last 18 months.

Many of these supply chain challenges stem from the disruption of international trade when factories and ports closed down in 2020. Now that the economy has opened back up, companies in the U.S. are waiting for inventory that may take many more months to arrive.

Additionally, companies with international suppliers face rising container prices. The average price to ship a standard 40-foot container globally has more than quadrupled to $8,399 since 2020, according to a July report from London-based Drewry Shipping Consultants Ltd.

Companies that have supplies in Asia have continued to work through the challenges, but are starting to look at suppliers in the U.S., Central and South America, Mexico and Canada as alternatives.

Jesse Morris

Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer, Main Street Capital

Anthony Nuzio, the founder and CEO of ICC Logistics Services, says many global supply chains were totally unprepared for COVID-19, despite warnings of supply chain vulnerabilities, like trade tensions between the U.S. and China that flared up in 2018. Today, all businesses must operate in an environment where they need to anticipate when the next disruption will occur, “because it will happen,” he says.

This includes shifting away from single-source suppliers. Businesses must seek out alternate suppliers and freight carriers to ensure there are supply options when the next disruption occurs, Nuzio says.

Many businesses rely on trade from Asia and elsewhere around the world for raw materials and components, but Jesse Morris, executive vice president and chief operating officer of Main Street Capital, says some of the firm’s domestic portfolio companies are seeing an uptick in demand as customers increase production and diversify their supply chain.

The phenomenon of U.S. businesses reworking their logistics networks by moving suppliers from overseas closer to the base of operations is known as “reshoring,” and Morris has seen it in motion over the last year as companies shift away from single-sourcing from Asia.

Morris says he’s seen some companies whose customers had been taking their products offshore before the pandemic. But severe disruptions in Asia and elsewhere caused certain customers to reset and bring portions of their supply chains closer to the U.S.

“Domestic manufacturers have seen a benefit from that,” Morris says. “Companies that have suppliers in Asia have continued to work through the challenges, but are starting to look at suppliers in the U.S., Central and South America, Mexico and Canada as alternatives.”

Moving ahead, ICC’s Nuzio says supply chain budgets will need to be more flexible to accommodate future disruption. He recommends quarterly budgets that have a reasonable amount of “wiggle room,” and suggests that supply chain leaders report directly to the C-suite. “Their decisions affect the fundamental operations and profitability of every business,” he says.

Alex Rabens, co-founder and CEO of Mickey, which helps manufacturers purchase and ship commodities and raw materials, recommends that company vendors or suppliers undergo request-for-quote processes every quarter to keep pace with changes in the logistics market.

“If your supply chain manager is choosing favorites or resisting the hassle of negotiation, you’re losing margin,” he says.

Supply Chains Go Digital

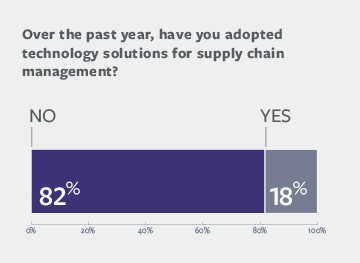

To minimize the disruption in current supply lines and increase resiliency, more companies are choosing to go digital.

BDO’s 2021 “Middle Market Digital Transformation Survey” showed that the pandemic pushed middle-market companies to accelerate their digital transformation strategies, particularly as they pertain to increasing supply chain resilience.

If your supply chain manager is choosing favorites or resisting the hassle of negotiation, you’re losing margin.

Alex Rabens

Co-founder and CEO, Mickey

The key to supply chain resilience is digitization. Robert Brown, a managing director of BDO Digital at BDO USA LLP, explains that digitalization includes companies adopting technological processes like data analytics, which can help identify inefficiencies in supply chains. Forty-three percent of companies are planning to digitize their supply chain in the next 12 months, according to the BDO survey.

Unfortunately, many companies don’t have great visibility into their supply chains. In a recent FreightWaves survey, 45% of shippers said they felt visibility of business operations was extremely less accurate or somewhat less accurate than their competitors.

To combat these problems, manufacturers are turning to technology. In 12 months, 87% of manufacturers will have digitized their supply chains, or be in the process, to increase visibility and agility, according to the BDO report. For retailers, that figure was 91%.

“Resiliency is about having a pulse on what the business is doing, what the industry is doing, and what the customers are doing, and how they’re reacting to the business,” Brown says.

He sees multiple areas where supply chain technology could pick up in the coming years, including artificial intelligence, the internet of things, and robotics and automation.

Blockchain—the technology undergirding cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin—is making significant headway in proving its business value, according to Rajat Rajbhandari, the chief information officer and co-founder of dexFreight, a cloud-based software provider.

DexFreight uses blockchain’s distributed ledger system to help companies select carriers, verify legal documents, negotiate freight costs and track shipments. Rajbhandari says the transparency and security blockchain provides, as well as the ability to offload back-office tasks and IT infrastructure to the cloud, help reduce costs for companies.

“We believe blockchain will usher in a new era of collaboration between [carriers] to reduce the cost of onboarding new suppliers, share cybersecurity threats, global identification, component traceability and more,” he says.

In an era of extreme weather events, companies with large exposure to the supply chain may also become dependent on services provided by DTN, a data, analytics and technology company that provides personalized weather and other actionable insights.

Advanced weather modeling and data science can allow companies to optimize land, sea and air shipping routes, which can avoid delays and lower fuel cost, according to DTN’s Vice President of Weather Operations Renny Vandewege.

“Hyperlocal weather data overlaid on road networks data can predict dangerous patches on roads and potential traffic conditions,” he says. “Weather analytics can also help manufacturers move their equipment to safer facilities or delay delivery based on real-time data.”

Tech for the Middle Market

While some technologies are being deployed by well-resourced large companies, it may take years for them to reach the lower end of the market, where a different sort of technological revolution is occurring.

Artificial intelligence and machine learning grab headlines and attention, but the reality of digitalization of supply chains tends to be much more grounded, especially for small and midsize companies.

“What you’ll see at our companies is more of tried and true technology,” says Main Street’s Morris.

Morris says the firm has invested in a software company that focuses on technologies that help companies be more efficient, like enterprise resource planning (ERP) software, manufacturing execution systems, warehouse management systems and e-commerce electronic data interchange that help manage data internally across their manufacturing and distribution operations, as well as across the supply chain.

Retail locations are now becoming mini distribution centers to ship inventory locally.

Robert Brown

Managing Director, BDO Digital at BDO USA LLP

But just because the data gathering and analysis may be less complex than other cutting-edge technologies, that doesn’t make implementing them easy. According to Morris, it could take between six months to a year to deploy an ERP or warehouse management system at a small company.

Nevertheless, ERP systems and other data-gathering software is becoming an increasingly critical component of any company’s logistics technology strategy, according to Chris Nicholson, CEO of Pathmind, a developer of advanced analytics tools for the logistics industry.

“Getting those systems to integrate smoothly to give you supply chain transparency is hard, but if you don’t do that, you can’t see what’s happening,” he says. “And, if you can’t see what’s happening in your supply chain, you’re never going to control it.”

Amazon set a high bar for supply chain efficiency, but it’s still within reach for middle-market companies.

For small and midsize retailers, BDO’s Brown says he’s seen a shift. When storefronts closed in March 2020, businesses moved to the only place where they could sell: the internet.

That shift to e-commerce posed a significant challenge for the logistics of retailers. “You can’t really be effective on a digital storefront if you have an ineffective supply chain,” Brown says. “If somebody places an order online and you have no ability to provide the product, then you’re not going to be generating revenues.”

But with physical storefronts open again, Brown says companies are taking the lessons learned during the pandemic and building on them to solve for inefficiencies they didn’t know they had until they went all-digital. There are now plenty of third parties that are providing affordable tools, enabling even the smallest retailer to have the same efficiency as a large company, he adds.

Websites like Shopify, Magento and Wix can be put up in a day and allow small retailers to sell products directly from a warehouse. “These technologies are being scaled down to the level that emerging companies can adopt and shift quickly,” Brown says.

However, that doesn’t mean storefronts are disappearing. The supply chain for retailers is now taking on a more hybrid role by offering both traditional brick-and-mortar and an online marketplace.

One trend Brown has noticed is retailers overhauling the physical layout of their stores to accommodate hybrid selling. Most retailers are expected to keep their brick-and-mortar locations open, but convert retail space to small warehouses—something Brown calls the “edge-based” supply chain.

“Retail locations are now becoming mini distribution centers to ship inventory locally,” he says.

Filling the Skills Gap

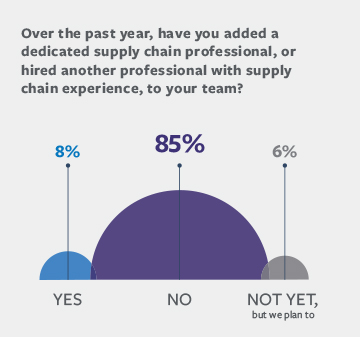

Identifying and implementing new technologies can be a good hedge against future supply chain and logistics risks, but they may end up going to waste without the right talent.

Brown finds that some middlemarket companies that adopt technologies like an ERP system only use 17% of features available. In those cases, he suspects the business has not made changes in any other areas.

“If you’re not efficient in your technology utilization, you’re not going to be efficient in what your customer experience and business outcomes are going to be,” he says.

That’s creating demand for business process experts, like data analysts, who understand ERP systems and other the technology. But Brown warns businesses of implementing technology solutions without engaged management teams in place.

“It’s like buying a car without any wheels on it, but you’ve got a fantastic drive train,” he says. “You don’t have the other pieces of technology that go along and make that an entire solution.”

Brown recommends businesses consult with subject matter experts and have business strategies and process experts in place to work in tandem with the technical experts.

“You’ve got to get a human involved in the decision-making, rather than just data gatherers,” he says.

Mickey’s Rabens says without a knowledgeable supply chain manager setting up and maintaining the chain, bottlenecks emerge rapidly and profit- margins quickly sink.

He adds that the requirements for supply chain managers were once stringent, but attitudes are changing as companies realize the importance of having resilient supply chains. “Having stints at many different companies used to be a resume red flag,” Rabens says. “But for supply chain managers, that is optimal. Hiring someone with 15 years or more at Amazon might know exactly how they do it, but not how to function in a new environment.”

In addition to technical staff like data analysts, Main Street’s Morris says the firm’s portfolio companies are also hiring project managers, process engineers and strong operations managers. That’s no different from what its companies were doing before the pandemic, but he says that both the current labor environment and supply chain disruptions make securing and retaining this type of talent more critical.

Morris also underscores the importance of retaining blue-collar talent in order to keep supply chains resilient.

There is an increasing demand for factory and warehouse labor, but many companies are facing shortages in available employees. Main Street’s companies have focused on rehiring employees let go in the early days of the pandemic and supporting training and onboarding initiatives.

Main Street’s current data gathering and analysis teams also have helped identify inefficiencies within its factories and warehouses to take employees where they’re not needed and place them in areas where they are, skirting some of the pressing labor shortages.

The firm’s companies have also focused on offering competitive wages and creating a company culture and work environment conducive to retention, which includes continuous improvement and communication.

Disruptions over the last 18 months have been so severe that Main Street’s strongest performing management teams are looking for employees with strong interpersonal skills to build relationships with customers, suppliers and others who will communicate early and often to anticipate and solve issues before they arise.

“There’s always going to be problems, but what the customer remembers is not the problem, but how you dealt with it, how you managed it, and how you tried to solve it,” Morris says.

Between May 28th and June 24th ACG surveyed more than 120 ACG members about work and technology.