In the Opportunity Zone

The opportunity zone program aims to stoke investment in underserved areas, but until investors receive clarifications, the program's impact remains unclear.

UPDATE: Following the publication of this story in Middle Market Growth, the IRS released a new round of opportunity zone guidance that provides additional clarification for some topics discussed in this story that could not be included at press time. For key takeaways, see the Public Policy Roundup published after these updates were issued or the original document released by the IRS for a complete account.

Lower corporate tax rates may have been the most celebrated aspect of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in the business community, but a new program created by the law has continued to attract investor interest, even as key parts of the provision remain undefined.

The opportunity zone program, which went into effect on Jan. 1, 2018, incentivizes investors to redeploy profits from the sale of property or investments. By investing their capital gains into economically disadvantaged communities, they can defer capital gains taxes and reduce their tax bill.

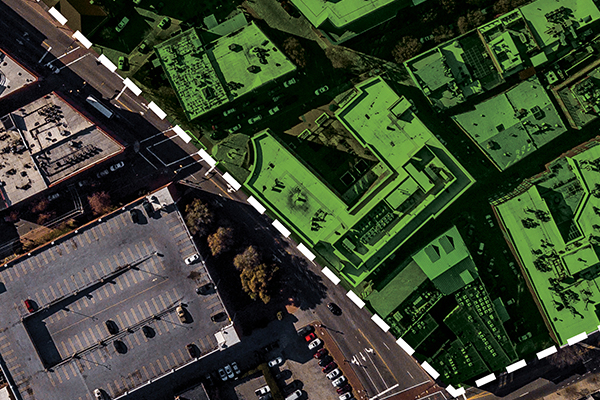

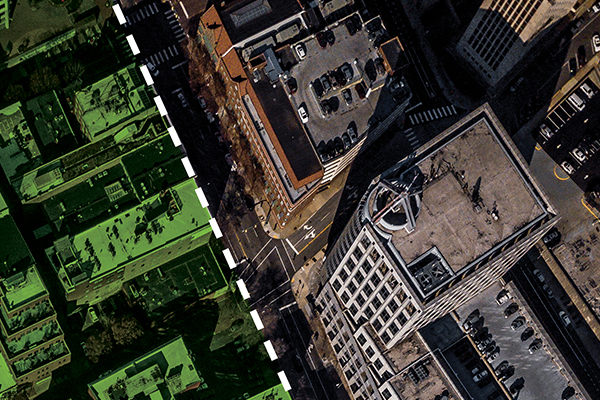

The program was intended to spread wealth beyond large cities and spur economic development in underserved regions across the United States and U.S. territories. Using census data, state governors designated more than 8,700 tracts as qualified opportunity zones. But despite the appeal of the tax and social benefits, many investors are biding their time as they await updated guidelines and determine whether the program fits with their investment model.

Others are moving forward using the available guidance. Funds currently in the market include a mix of real estate and private equity-focused vehicles targeting opportunity zones. Alongside dedicated funds, family offices and other sponsors are making direct investments in zones where they see potential for high growth.

Real estate funds were the first movers, in part because the real estate industry is already set up to maximize tax incentives. For private equity, capitalizing on opportunity zones has been harder. Most PE firms and sponsors of operating businesses are in a holding pattern as they await updated guidelines from the Treasury Department and the Internal Revenue Service about which investments qualify under the program.

As currently written, the opportunity zone regulations require a business to operate and generate revenue within a zone. Those rules are easy to interpret as they relate to a barbershop or a nail salon, but they’re less clear for a software company or a provider of distribution services. The program was designed to bring economic development to underdeveloped areas and keep it there, but it can be challenging for a company to prove it meets the qualifying criteria when the jobs it creates go to knowledge workers, or when it sells its products online.

“Right now, there’s a blend of optimism and uncertainty on the business side,” says John Lore, managing partner at Capital Fund Law Group, based in New York. He expects the new guidelines, which likely will be released this summer, will bring added clarity about what it takes for a business to qualify for opportunity zone funding. Even then, PE investors will have other questions to reckon with. “Once the regulatory questions are answered, private equity’s real work begins: picking the individual projects that will be successful within a given zone,” he says.

There are also questions about whether a company qualifies for investment after it scales to multiple locations, including areas that may be outside a zone. For that reason, venture capital could have an advantage over private equity when it comes to opportunity zones—venture sponsors can start with a small company that needs time to build up in its current location.

“RIGHT NOW, THERE’S A BLEND OF OPTIMISM AND UNCERTAINTY ON THE BUSINESS SIDE.”

JOHN LORE

Managing Partner, Capital Fund Law Group

Craig Bernstein, founder of OPZ Capital, a private equity fund dedicated to opportunity zone investments, points to another way PE firms can participate in the program. Once the guidelines have been clarified, PE firms may be able to invest in businesses that are already located in an opportunity zone by doing a material redevelopment that would meet the compliance requirement. “You could see firms do some site and operational improvements that are significant enough to meet the threshold,” he says.

NARROWING THE FIELD

Not all opportunity zones are created equal. The zones were designated based on 2010 census data, the most recent aggregate federal data on nationwide demographics. But a lot can change in a decade. Oakland, California, for example, has opportunity zones, but the city today looks much different than it did in 2010. As the tech industry has continued to soar, rents have skyrocketed while other local assets command a premium. Over the 10 years since the last census, other cities like Denver and Austin have flourished and are now growing rapidly. Opportunity zones within their city limits may end up adding fuel to the fires rather than creating tiny sparks nationwide.

But for a firm looking for strong returns, investing in a fast-growing city can feel less risky than betting on an economically depressed area. “For us, of those 8,700 or so tracts, a subset of them are investable,” says Brett Messing, a partner at SkyBridge Capital, which launched an opportunity zone fund this year with subadviser Westport Capital. The fund is looking at a combination of industrial projects and multifamily housing.

Messing notes that the economics are best in cities where there is pent up demand for construction. “I still have PTSD from 2008, but nationally, we’re under-homed. We’re looking at secondary cities—Savannah, Nashville, areas that are growing fast and need supply,” he says. “There are firms out there in cities that aren’t seeing massive growth yet, working from a ‘build it and they will come’ thesis, but we are going forward conservatively.”

Messing’s comments reflect the mindset of many fund managers and business operators. While the tax deferral incentives with opportunity zones are significant, for a number of investors the program is still primarily a means of offsetting up-front capital costs. Projects still have to work on paper, and that case is harder to make in an area that isn’t already on a growth trajectory.

Regulators tried to work around some of these concerns by requiring funds to invest over a 10-year investment period in order to realize the full tax incentive (although partial benefits are available for shorter investment durations). The law sought to draw patient capital that could help cities overcome obstacles to growth, a strategy that isn’t entirely new: Using tax incentives to attract private capital dates back to the 1970s, when legislation like the Community Reinvestment Act and the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act pursued similar goals, with mixed results.

Chris Loeffler, CEO and co-founder of real estate investment firm Caliber in Scottsdale, Arizona, says the structure of the opportunity zone program has opened the door for collaboration with municipalities that want to approach projects in a new way. “We’re getting cities coming to us now and saying, ‘This our land, these are our goals, how can we work with you?’ That’s not usually the case for developers. So we are taking advantage of that.”

That willingness among cities to think outside the box can mean more mixed-use developments or arrangements where funds invest in a real estate project and then work with retail tenants for a small interest in the revenue. Entertainment and hospitality projects have also emerged as key targets.

Working alongside local investors is another approach, one that family office McNally Capital is employing as part of its Capital Across America strategy.

“We’re working in several cities and partnering with local families that understand those communities,” says Frank McGrew, managing partner at McNally, which invests in real estate and operating businesses within opportunity zones directly, rather than through a fund. “They are often interested in supporting the business investment side and real estate because of those local ties. They understand what the total opportunity set is.”

EXPANDING IMPACT

Much of the activity around opportunity zones is still centered on vetting deals, finding sites and setting up what will eventually be a project pipeline. Still, some early movers are breaking ground. Virtua Partners, a global PE firm focused on tax-advantaged investment strategies, plans to open a Marriott-franchised hotel in the Phoenix metro area this summer. The project is one of the first near completion. According to Quinn Palomino, Virtua’s co-founder, the project stands on its own and would have been done regardless, but the opportunity zone structure sped up financing.

Virtua won’t invest in a deal unless the firm feels like it’s a solid transaction, not just an “opportunity zone deal,” according to Palomino. She adds that for the opportunity zone program to achieve its goals, there needs to be a way to evaluate what communities need and how private capital investments have or haven’t helped. That means establishing metrics for tracking opportunity zone deals and the types of jobs they generate and creating greater transparency around these investments.

“IF YOU HAVE A BAD DEAL AND IT’S AN OPPORTUNITY ZONE PROJECT, THERE IS THE POTENTIAL FOR OTHER OPPORTUNITY ZONE PROJECTS TO BE JUDGED IN THAT WAY.”

QUINN PALOMINO

Co-Founder, Virtua Partners

Palomino describes Virtua as both a firm focused on tax-advantaged strategies and a longterm investor that supports community development. She says the success of the program could hinge on the quality of investments made. “If you have a bad deal and it’s an opportunity zone project, there is the potential for other opportunity zone projects to be judged in that way,” she says. “There is a lot of attention focused on this space.”

Palomino emphasizes the potential for longterm hospitality careers to result from Virtua’s hotel investment. Darryn Jones, vice president of business development at the Greater Phoenix Economic Council, who worked with Virtua on the project, adds that the city is collaborating with other businesses to build up tourism around the hotel site as a way of expanding the impact throughout the zone.

City and state officials in Arizona also plan to modernize business incentives for companies that want to operate in the area but do not qualify for funding through opportunity zones. “Municipalities in our area are being aggressive about educating businesses and landowners on what the options are with opportunity zones and other incentives,” Jones says. Meanwhile, they are increasing their outreach to attract companies in leading industries.

While it’s still too early to predict opportunity zones’ overall impact, many municipalities are using the incentives to step up their marketing efforts the way Arizona has. Raising awareness could attract local firms that can make new investments—even if big-name PE funds aren’t yet ready to invest.

This story originally appeared in the May/June print edition of Middle Market Growth magazine. Read the full issue in the archive.

Bailey McCann is a business writer and author based in New York.