How Canada Became a Midmarket Tech Destination

American investors were once a rare sight in Canada. Now, an increasing number are finding plenty of tech opportunities north of the border.

A decade ago, Doyl Burkett flew to Ottawa to research an investment. It was the first time he visited Canada, and he was surprised by his reception—people hugged him in thanks for coming.

At the time, American investors were a rare sight in Canada. “A lot of U.S. investors won’t even go there,” says Burkett, co-founder of Integrity Growth Partners, an investment firm based in Los Angeles. “There’s this mental block, one we’ve found is very lucrative to overcome. There are a lot of great opportunities there. But for whatever reason, historically, there just haven’t been as many people going up there. Which is good for us.”

Since then, Burkett and his co-founder, Scottie Wardell, have continued investing in Canada. They’ve found success in their niche of owner-run, midmarket software and technology companies.

But recently, investors from across the world have started investing in Canadian tech. It’s good news for Canadian businesses, Burkett says, but a net negative for investors who held Canada as a well-kept secret.

Secret No More

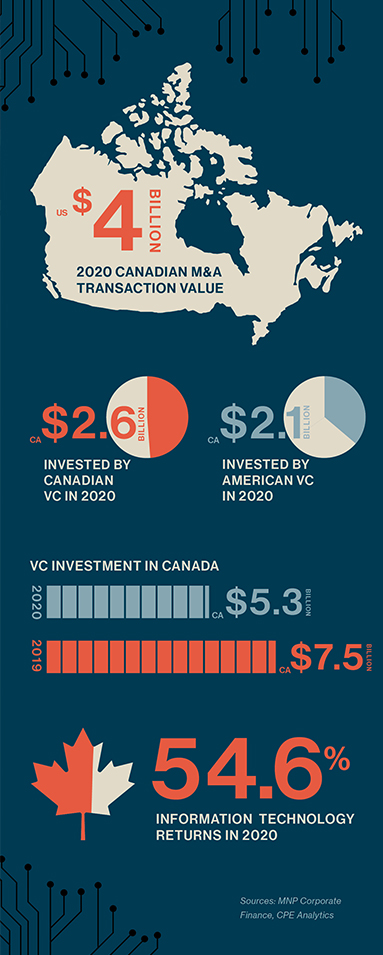

Despite the pandemic, 2020 was a big year for private capital investment across Canada, according to CPE Analytics’ Canadian Venture Capital Report. Venture capital investors disbursed $5.3 billion Canadian dollars to Canadian companies in 2020, a slight dip from 2019 when investors set a record with CA$7.5 billion in disbursements.

The numbers in 2020 were lower than they’d be if there was no pandemic, as U.S. investors pulled back a bit, but Canadian venture capitalists spent more than usual. Canadian investors disbursed CA$2.6 billion in 2020, while U.S. funds invested CA$2.1 billion.

And investments surpassed expectations. International Data Corporation predicted in March 2020 that the pandemic would substantially slow the Canadian tech market. But beyond a few weeks at the start of the pandemic, Shevaun McGrath, partner and co-head of private equity at Canadian law firm McCarthy Tetrault, says that the midmarket tech sector was stronger than ever, especially for software and health care tech.

Mergers and acquisitions deal value and volume also rose, according to MNP Corporate Finance’s Middle Market M&A Update for Q4 2020. During the early days of the pandemic, there were $2.7 billion worth of transactions— by the end of the year, they were up to $4 billion. Technology did especially well in the midmarket, with information technology rising 7.4% in Q4. IT was the best performing segment of the year, with a return of 54.6%, largely because of companies developing e-commerce platforms.

After a strong showing last year, McGrath believes that the midmarket Canadian tech industry will keep growing.

“It’s crowded for a reason,” she says. “Because the assets are so attractive.”

A Brief History of Increasing Competition

Canada wasn’t always such a hotbed of tech. In the early 2000s, Canadian investor Jim Orlando described it more like a nuclear winter.

After the dot-com bubble exploded, Canadian investors were decimated. “You had, in a sense, a bunch of first-time funds that never made it onto fund two,” Orlando says. For years, there was little investment in Canada’s tech industry— even Orlando went to work in Silicon Valley.

But something changed around 2010. Tech giants, such as Microsoft and Amazon, opened R&D hubs across Canada—Orlando believes that they were drawn in by Canada’s talented computer science graduates. McGrath echoes this, noting that the University of Toronto and University of Waterloo have well-regarded computer science programs, which make for attractive human capital.

In 2013, the Canadian government wanted to break the country out of its nuclear winter. It offered investors a program called the Venture Capital Action Plan. This program deployed $390 million in capital to venture capital and private sector funds across the country, which then invested that money in Canadian businesses.

Then, in 2015, one of Canada’s home-grown startups, Shopify, went public. It proved that Canadian tech companies could grow large. Orlando—who had become an early investor in Shopify as a managing partner with OMERS Ventures in Toronto—said that investors became more confident about Canadian tech. More importantly, so did Canada’s entrepreneurs.

Then, in 2015, one of Canada’s home-grown startups, Shopify, went public. It proved that Canadian tech companies could grow large. Orlando—who had become an early investor in Shopify as a managing partner with OMERS Ventures in Toronto—said that investors became more confident about Canadian tech. More importantly, so did Canada’s entrepreneurs.

“That was a really meaningful moment in the Canadian technology industry,” Orlando says. “You had a standalone, independent, Canada-founded startup that went on to dominate its segment and go public on both the Toronto Stock Exchange and the New York Stock Exchange, simultaneously. That became a sign that this can actually happen in Canada.”

Orlando, who now serves as managing partner of Canadian venture capital firm Wittington Ventures, says that the Canadian tech market has matured over the past decade. Many Canadian tech entrepreneurs have gone on to found their second and even third business, something that would have been unusual 10 years ago.

And the nuclear winter appears to be over. There are now more investors like Burkett and Wardell from outside Canada, but also many more Canadian investors like Orlando.

“It gives more opportunities for Canadian investors to invest in Canadian companies,” Orlando says. “Once you get into this midmarket range, all the growth equity shops in the U.S. don’t even think about the fact that there’s a border. They’re looking at companies in Silicon Valley, just like they would look at a company in Chicago, just like they would look at a company in Toronto. They wouldn’t distinguish on a geographic basis.”

“Once you get into this midmarket range, all the growth equity shops in the U.S. don’t even think about the fact that there’s a border.”

Jim Orlando

Managing Partner, Wittington Ventures

Why Investors Love Canada

In Canada, relationships matter. Burkett and Wardell say that relationship-building is a cornerstone of their strategy in Canada, and a perk of working in the country. Everyone in the market seems to know each other.

This is far different from U.S. tech hubs. Doing business in Silicon Valley feels like being a contestant on “The Bachelor,” Burkett says. Companies often send a page to collect the top bids, then decide on their partner from afar. But doing business in Canada’s midmarket requires getting to know people and forming relationships. It’s a market where reputations are made by way of social inroads.

For U.S.-based investors in a foreign country, this matters greatly, especially since Canada isn’t quite so foreign. Jake Brodsky—a principal at San Francisco-based private equity firm Alpine Investors and co-founder and principal of Alpine Software Group (ASG), Alpine’s software-focused arm—says that the people and systems in Canada were a great cultural fit, something that was helpful for understanding the market, companies and employees.

Although Canada feels familiar, U.S. investors will still face challenges on foreign turf. Some of the grants and tax credits offered in Canada, for example, aren’t transferable if an investor moves a company away from Canada.

U.S. investors will also need to become aware of Canadian law, McGrath says, like the Investment Canada Act, which requires government approval for transactions of a certain size. Investors may be familiar with the law’s American counterpart, the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States.

“If the government determines that there are national security interests, then they can block the deal. In the tech industry, we’re really careful to ask, question No. 1, ‘Who are your customers?’” McGrath says. “Even if it’s printer delivery, or something silly like that, our government has been very active in using their national security review process to put their finger on stuff that they think may be a national security issue.”

But the main challenges lie at the crossroads of increasing competition and the need to form strong relationships. If an investor doesn’t have relationships in Canada, they’re starting from nothing. Brodsky’s advice: Find a “river guide,” someone who knows the Canadian market. Brodsky leans on executives at a company his firm invested in when he has questions.

“If interest rates stay the way they are, if the bright minds of Canada keep producing stuff that we’ve never even thought of, I think the demand will remain.”

Shevaun McGrath

Partner and Co-Head of Private Equity, McCarthy Tetrault

Wardell advises staying true to your niche. For Integrity Growth Partners, that’s the lower middle market, which has more companies and less competition. “You can still distinguish yourself and get to know these folks,” she says. “That has allowed us to stay competitive and win really good deals in a market that’s already quite competitive.”

What Does the Future Hold?

Orlando believes that investment in Canada will be slower in 2021, due to lingering effects of the pandemic. But he expects the market to pick up when more people are vaccinated and the Canadian border reopens. That might take a while, due to a turbulent start to Canada’s vaccine rollout. Only 2% of the population was vaccinated by mid-April, compared with 25% of U.S. residents, according to Oxford University’s Our World in Data.

Burkett and Wardell predict that pent-up demand will drive significant growth in the coming years. Even so, they’ll be watching whether certain types of companies that were successful amid the crisis—education technology, for example—can maintain their success.

McGrath expects Canada’s midmarket tech sector to be strong for a long time. While there are always ebbs and flows in markets, she doesn’t see ebbs coming anytime soon.

“If interest rates stay the way they are, if the bright minds of Canada keep producing stuff that we’ve never even thought of, I think the demand will remain,” McGrath says. “Canada is a nice, stable economy to invest in, and the global interest will remain. I don’t see it ending anytime soon.”

Hal Conick is a writer based in Chicago.

There are other perks of investing in Canada’s middle-market tech sector, investors say, including:

Smaller markets. Doyl Burkett and Scottie Wardell cover companies in over 195 cities in Canada, but the vast majority come from Toronto, Vancouver, Montreal and Calgary. Focusing on these major metropolitan areas is more manageable— as Canada’s land mass is huge—and also lucrative. Toronto alone took in more than CA$1 billion in investments last year, according to the 2020 Canadian Venture Capital Report.

Less competition. While the competition in Canada’s tech sector is picking up, investors in Canada will compete with far fewer investors than they would in California.

Talented university students. Investors have noticed Canada’s talented workforce, but also its students. Jake Brodsky says that the Canadian government incentivizes Canadian graduates unlike anywhere else he’s visited. Many students come from overseas and the Canadian government entices them to stay after graduation.

Companies invest in students, too. One company Brodsky invested in works with engineers as they continue to earn their degrees. “Afterwards, they’re getting full-time offers to come and stay within our company and continue working on the product,” he says.

More foreign workers. Since 2016, many foreign workers opted for Canada over the U.S. amid the Trump administration’s limits on foreign work visas. Meanwhile, the Canadian government’s Global Skills Strategy program works to draw in foreign workers, often processing work visas within two weeks.

A stronger U.S. dollar. It’s easy math for investors: At press time, the exchange rate is 1 U.S. dollar for every 1.21 Canadian dollars.

Tax credits. Tax credits may be the biggest perk of doing business in Canada. For example, the Canadian Scientific Research and Experimental Development Tax Incentive Program, or SR&ED, offers an investment tax credit of 35%, up to the first $3 million, for research and development by companies working in technology, design, data and related fields.

“It basically takes on the cost for a company and allows them to become the bootstrapped company we’re looking for,” Burkett says. “If I’m spending $1 million in R&D in the U.S., that’s coming out of my pocket and it’s gone. In Canada, depending on how you spend it, you’re going to get a decent portion back. You can extend your runway longer in terms of burning capital and not having to raise capital because of SR&ED.”