The Middle Market’s Next Frontier

Space was once the exclusive domain of publicly funded initiatives and startups, but declining costs are opening it up to midsize companies and investors.

This article originally appeared in the November/December 2020 issue of Middle Market Growth.

At his home office in Boca Raton, Florida, Marc Bell picks up a polished black box from his desk.

“This is why the world changed,” says the founder, president and CEO of investment firm Marc Bell Capital Partners, holding something a little bigger than a Rubik’s cube. “This is what made space travel affordable.”

Weighing around six pounds, the pint-sized satellite in Bell’s hand was designed and built by Tyvak Nano-Satellite Systems, a subsidiary of Terran Orbital, of which Bell is co-founder and chairman. A version of the satellite platform, the Trestles 6U, launched into orbit in December 2019, and it’s one of the innovations leading more companies into space by drastically reducing the weight—and therefore cost—of getting into orbit.

Not long ago, space was the exclusive domain of publicly funded initiatives and a few large private players, but declining costs from breakthroughs like Tyvak’s miniature satellite, SpaceX’s partially reusable Falcon 9 rocket and the development of in-orbit manufacturing are opening up space to more private companies and drawing interest from investors.

A 2018 estimate from the Space Frontier Foundation, an advocacy group that supports the private space industry, valued the total annual revenue generated by companies that produce spacecraft or collect and analyze satellite data at around $350 billion. Reports from Goldman Sachs, Deloitte and Morgan Stanley project the space industry could reach $1 trillion to $2 trillion by the 2040s.

Investors have spotted the opportunity. In 2019, there were 159 disclosed deals in the space technology sector, a nearly 10% increase from the year before, according to data from PitchBook. One of the largest deals was the $110 million venture round for the Sierra Nevada Corporation, a designer and maker of hardware like space suits and spacecraft components.

Despite a downturn in M&A due to the pandemic, this year’s deals include the $1.64 billion acquisition of satellite imaging firm Dynetics by Leidos, an aerospace and defense company.

Filling the Middle Space

Like many cutting-edge industries, the space technology industry has a bookending problem. Peter Cannito, chairman and CEO of Redwire, a spacecraft component manufacturer, describes it as akin to a barbell: big companies on one end, early-stage ventures on the other, and not much in between.

“You either have large, legacy aerospace organizations that struggle to adapt rapidly enough to new innovation, or small companies that don’t have the scale to take on major programs or move disruptive technologies into production,” Cannito says.

The imbalance between startups and incumbents also poses a challenge for investors, he adds. “It means you have to invest in too many small transactions in order to move the needle, and there are no new entrants capable of producing above-average returns at scale.”

Redwire’s goal is to fill the middle- market gap in space technology with a company small enough to innovate rapidly, but large enough to finance major programs and production contracts.

Cannito joined Redwire shortly after it was created in March by AE Industrial Partners, a private equity firm that invests in midsize aerospace and manufacturing companies.

A former operating partner at AE, Cannito joined Redwire to manage its acquisitions, the first of which came in March with Adcole Aerospace, a nearly 60-year-old company that had produced components for most major NASA space missions, including the Perseverance and Ingenuity Mars missions that launched in July.

In June, Redwire acquired aerospace designer and manufacturer Deep Space. A few weeks later, it announced the acquisition of Made In Space, a company that got its start working on the International Space Station, developing techniques to manufacture components in orbit.

Cannito draws parallels between Redwire’s motto, “Heritage Plus Innovation,” and its goal of taking companies that excelled in one area and integrating them under a single platform.

“We don’t consider ourselves to be just a new space disrupter,” he says. “Our thesis is to combine flight heritage with some of the disrupters to fill that middle-market gap.”

The combination of legacy companies like Adcole and new players like Made In Space enables Redwire to carry out large-scale programs, like the 2020 Mars mission, while also fostering innovations like in-orbit manufacturing and miniature components for spacecraft.

Private Equity’s Opportunity

Only a handful of private equity firms have a presence in the industry, and they tend to be big players like Blackstone, which bought a space-based optics business from defense giant Raytheon in April. But the continued commercialization of space and a market that has yielded many stable, late-stage startups is changing that.

We don’t consider ourselves to be just a new space disrupter. Our thesis is to combine flight heritage with some of the disrupters to fill that middle market gap.

Peter Cannito

Chairman and CEO, Redwire

“It’s become an opportune time for private equity to invest,” says Kirk Konert, a partner at AE. “The market has matured enough for the industry-focused firm to find interesting opportunities, companies and teams to back.”

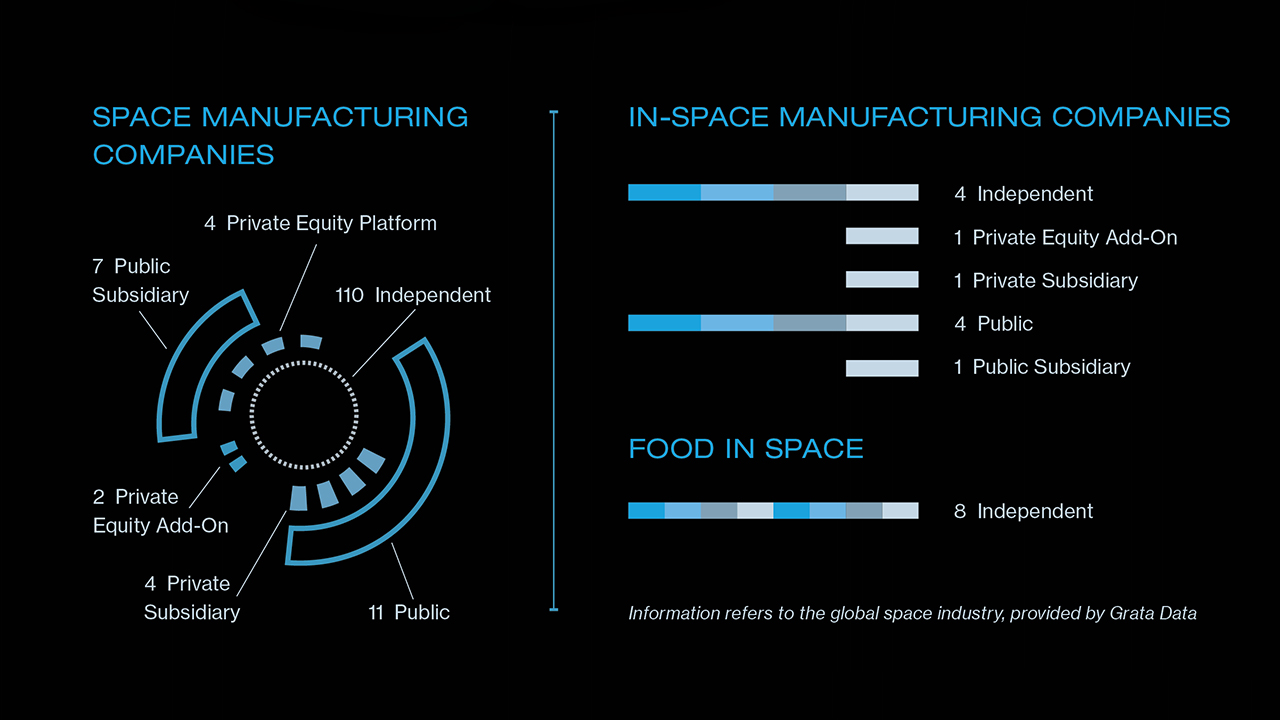

At press time, there are more than 100 independently owned companies that manufacture components for the space industry, including 90 based in the U.S., that could make attractive targets for investors, according to Grata Data, a company search engine.

Konert adds that AE is bullish on recent developments shaping the space industry, like SpaceX’s launch of the first manned mission completed by a commercial organization in May, and the creation of the U.S. Space Force, which was established in December 2019 to protect the growing number of assets in orbit. “We’re going to certainly be active,” Konert says.

Launching the Space Economy

Konert and Cannito expect Redwire will continue working with government agencies like NASA and the Department of Defense to generate consistent cash flow. Over the long term, they want to expand the company’s customer base to include other commercial entities.

Redwire has taken note of several high-profile setbacks in the industry, including bankruptcy filings by satellite communication providers OneWeb and Iridium Communications, whose business models proved costlier and less lucrative than expected, according to Cannito.

“Physics will get you to space, but economics will keep you there,” he says.

It’s become an opportune time for private equity to invest. The market has matured enough for the industry-focused firm to find interesting opportunities, companies and teams to back.

Kirk Konert

Partner, AE Industrial Partners

To ensure it remains financially sustainable, Redwire is looking to provide companies with infrastructure— new space-based communications and capabilities to manufacture components in orbit—something it hopes to achieve with its Made In Space acquisition.

In-orbit manufacturing could significantly reduce the cost to launch satellites and expand their capability. A satellite that can print its own solar panels or antennae in orbit could generate more power and have greater communications capacity in a smaller package, Cannito says, and could be the key to unlocking larger projects like commercial research and development outposts, and resource extraction on the moon.

Although private equity is still relatively new to the space industry, firms like AE Industrial are entering on the heels of early investors, like Marc Bell, who helped pave the way. In 2015, Bell was among the first to commit seed funding that got Made In Space off the ground.

Bell has been involved in the space technology industry since the 1990s, and his companies have since put over 220 satellites in orbit. His current venture, Terran Orbital, a provider of nanosatellite and microsatellite services, has raised tens of millions from investors that include Lockheed Martin, Beach Point Capital and Goldman Sachs since it was founded in 2013. Today, the company has around 125 employees. Its subsidiary PredaSAR announced in August that it will partner with SpaceX to deploy the first of 48 planned satellites next spring to collect data about activity on Earth’s surface—from weather and agriculture to traffic and energy extraction.

Over his 30-year involvement in the industry, Bell has seen how the miniaturization of satellites changed the economics of space. The influx of capital from investors like AE Industrial is now funding further innovation, like in-orbit manufacturing, an advancement that Bell expects will help shape the future of the space industry.

“It’s definitely going to start changing things,” he says. “We’ll know when you can lay out on the beach on Mars.”

Benjamin Glick is Middle Market Growth’s associate editor.